Windows of men’s souls

Tenor Jonathan Hanley explores the context of William Byrd’s life and music ahead of our anniversary concerts.

William Byrd is probably the most famous of all of the wonderful English composers of the sixteenth-century, and for good reason - his music is full of character, imagination, and pathos, and a watershed in compositional style for vocal music in England.

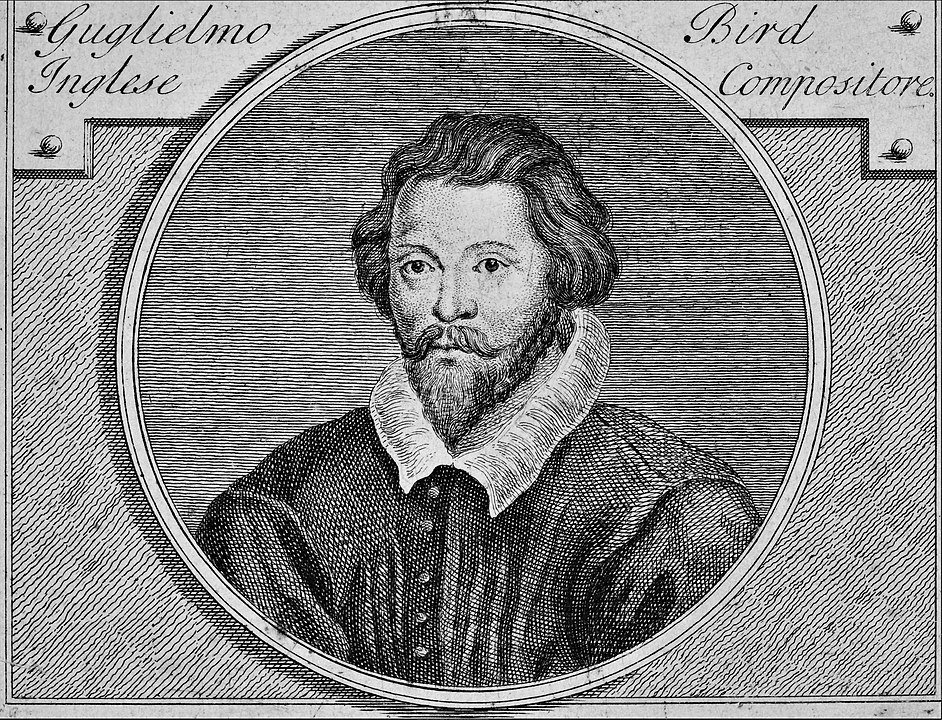

Etching by Gerard Vandergucht (British Library), Public Domain

The 400th anniversary of Byrd’s death in 2023 has seen a fantastic celebration of his work across the world. The thrilling tale of pieces written for secret services in great houses with priest holes and the ever-present threat of persecution is a fascinating accompaniment to his magnificent music. That the work of a man who gave voice to those in his community who were unable to speak continues to resonate with musicians and audiences alike 400 years later, is an even more compelling reason to celebrate Byrd.

“Byrd was risking not only treason but also heresy if he put a foot wrong. ”

His experience was a unique one. Whilst he enjoyed the patronage and protection of a Catholic aristocratic house in his later years, he spent the heyday of his career in London, not only working for the protestant Elizabeth I, but enjoying her benefaction and favour while writing works that were clearly evoking and sympathising with the plight of Catholics persecuted for their faith. Publishing three settings of the Latin mass in the 1590s under his own name was not only brave and bold, but a defiant act. Unlike Shakespeare, who also got away with a certain amount of artistic license, Byrd was risking not only treason but also heresy if he put a foot wrong.

The opening of the Cantus part from Byrd’s Mass for Four Voices (IMSLP)

Edmund Campion by J.M. Lerch; Antwerp (British Library)

Elizabeth had famously said on her accession that she didn’t desire to ‘make windows of men’s souls’, a sixteenth-century version of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell.’ After two reformations and a reversion to Catholicism in less than 20 years, Elizabeth saw that there was clearly a need for compromise, as long as nobody made a scene. The threat of persecution from a Queen whose religion and politics were so intertwined and changeable can never have been far away though. There are famous examples of those Elizabeth martyred for their faith – Byrd’s friend Edmund Campion for one – though, by and large Elizabeth was much more tolerant than her sister, Bloody Mary.

This tolerance seems to have been based on pragmatism and an ability to adapt and play the game. The first archbishop of her new Anglican church was Matthew Parker, a Protestant who had played a convincing enough part to survive the purges of England under Mary, Elizabeth’s sister. Byrd, whilst a Catholic, knew how to keep his head down in Elizabeth’s protestant England, and therefore enjoyed her support. He worked as a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, and he and his friend and teacher Thomas Tallis were given a monopoly on printing music in England. He was clearly a man, like Tallis, who understood how faith, politics and loyalty intersected.

“There is much that is unspoken in Byrd’s work”

Clearly the great contradiction in Elizabeth’s policy was that through her patronage, she allowed Byrd to open a window into his own soul through his incredible music, giving voice to so many who were in his position. There is much that is unspoken in Byrd’s work in the texts he chose to set, the importance of his rhetoric and the way he highlights the most significant passages. Many of the texts make reference to contemporary Jesuit works, which means that many of these pieces, when heard or performed by Catholic households in domestic settings, would have taken on additional meanings. It’s clear that Byrd is at his best in large-scale, plangeant and nostalgic outpourings like Infelix ego or Ne irascaris, and he manages to give voice to both a personal and communal grief in his style.

In 2022, SANSARA commissioned a piece of music written by Ukrainian composer Natalia Tsupryk. A Quiet Night - Tyhoyi Nochi sets text by renowned Ukrainian poet Serhiy Zhadan and quotations from one of President Volodymyr Zelensky’s many powerful speeches. Like the music of Byrd, Natalia’s piece is a musical expression of solidarity, a vehicle for compassion and reflection and a catalyst for connection. We’ve been overwhelmed and uplifted by the response to Natalia’s beautiful music, and the many communities around the world that have performed the piece and shared their experiences with us.

“after darkness I hope again for light”

The final section of Libera me Domine, et pone me juxta te, one of the pieces we’ll be performing in our upcoming concerts, sets the text ‘after darkness I hope again for light’. This universal and human prayer is at the heart of much of Byrd’s work and still resonates four centuries after his death, giving voice to those who need hope for a new dawn.

- Jonathan Hanley

We’ll be performing our anniversary programme Before the Dawn in the first week of July - find out where and book tickets via the link below:

We’ve put together a Spotify playlist for our programme which you can listen to below:

Matthew Johnson Photography